Sleep readiness is the ability to understand the importance of sleep to mission-essential tasks and apply good sleep hygiene to get the sleep you need for optimal health, well-being, and performance optimization. But many find it hard to get enough sleep to perform at their best. For example, trying to drive a vehicle on an empty tank isn’t a good idea. But many people routinely “operate” on little or no sleep. Many believe they can overcome being tired or “get used to it.” But evidence suggests that, for most people, getting 6 hours of sleep or less can jeopardize their performance, resilience, health, and well-being. As people become more sleep-deprived, they become less aware that they’re impaired.

When someone says, “I’m used to being tired,” they’re simply used to their impaired awareness and judgment.

This article covers the impact sleep has on your Total Force Fitness (TFF) and performance, includes tips to improve your sleep readiness, and provides useful tools and tips to help you make sleep a priority. If you are here because you already know the importance of sleep but want to improve your sleep, skip down to the section “How to improve your sleep readiness.”

Sleep readiness and Total Force Fitness

The Total Force Fitness framework promotes 8 interconnected domains of fitness—physical, nutritional, spiritual, psychological, financial, spiritual, environmental, and medical and dental—as a means to performance optimization. While sleep itself isn’t a domain of the TFF wheel, it falls under the domain of mental fitness. However, it directly impacts your performance across all the TFF domains, with examples below that address mental, social, spiritual, nutritional, and physical fitness. Your awareness of how sleep loss affects your performance is crucial to building healthy sleep habits.

Sleep helps you grab control of your emotions. During your day, you might experience events that trigger positive and negative emotions, but a good night of sleep helps bring those emotions back to baseline levels. You wake up feeling refreshed and ready to face a new day. But when you don’t get enough sleep, you might experience mood imbalances and difficulty regulating your emotions. For example, it gets easier to feel irritated, angry, or frustrated and harder to enjoy achieving a goal. Also, when you get a lack of sleep you might find yourself acting impulsive, with an increase in reward-seeking and risk-taking behaviors.

Sleep helps you manage stress. Many different factors during your day can activate your stress-response system. This is another change in your brain and body that links to the ideal set point during sleep. However, Warfighters commonly cite stress as the reason they experience problems such as sleep loss, nightmares, and insomnia. Sleep and stress are often connected in a vicious cycle: Stress causes sleep loss, making you feel more vulnerable to stress, which leads to even more sleep loss and reinforces activation of the stress-response system. The tips highlighted later in this article can help you break free from this cycle. Without enough rest and recovery, it’s more likely that the emotional and psychological coping mechanisms that help you manage stress won’t work as well as they should.

Sleep improves your mental readiness. Sleep also impacts your ability to think clearly, focus attention, process information, make decisions, and learn. When you learn something new during the day, the new knowledge gets stored in your memory while you’re sleeping. Therefore, adults and children who sleep well learn better. Sleep is also important for the physical health of your brain. While you’re in deep sleep, your brain works to dispose of waste—proteins and metabolic byproducts—that can lead to brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Fatigue from lack of sleep can cause you to fall asleep on duty, make errors, or get involved in operational accidents. Sleep loss seriously impairs your working memory, ability to concentrate, situational and battlefield awareness, focus, hand-eye coordination, reaction time, decision-making, and multitasking abilities. Lack of sleep is equivalent to being drunk. In fact, after being awake for 24 hours, you’d function as if you had a blood-alcohol content of 0.1%, which is legally drunk in most states.

Sleep empowers your social and spiritual readiness. Getting enough sleep is essential to your ability to self-regulate and live out your values. All the mental-health benefits of sleep directly impact your relationships and your ability to strengthen your spiritual core. Sleep loss also gets in the way of your ability to interpret people’s facial expressions accurately—specifically, if they’re happy, frustrated, or calm—making it harder to identify what they’re feeling. Therefore, sleep loss can impede your ability to empathize, understand what others are expressing, and maintain healthy relationships. Sleep loss also reduces trust and increases aggressiveness, tendency to blame others, unethical behavior, and deception. These changes affect your ability to communicate effectively and solve conflicts, having a negative impact on your personal and professional relationships. Studies in military settings show that sleep deprivation has a negative effect on group performance and unit morale and cohesion.

Sleep promotes physical health and performance. The progressive drops in heart and breathing rates that come with good sleep allow your heart and lungs to rest and improve your cardiovascular health. Likewise, the deep muscle relaxation you experience during sleep helps you heal from injury, recover from intense exercise, and maximize muscle gains. Sleep also replenishes the immune system, which helps prevent infections and malignancies.

When you don’t get enough sleep, you’re vulnerable to the opposite: slow recovery from physical injury, greater sensitivity to pain, weakened immune system, and frequent infectious diseases. Chronic sleep deprivation also increases your risk for hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic imbalances, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Sleep loss can also affect your physical readiness and performance and increase your risk of injury. In addition to reducing your motivation to exercise, lack of sleep impairs motor coordination, balance, accuracy, reaction time, and acquisition of new motor skills.

Sleep regulates your hormones and eating habits. Sleep balances many factors that control hunger, including hormones, circulating glucose, and the gut microbiome. Lack of sleep can cause imbalances of the hormones that regulate your hunger and appetite, so you’re more likely to crave junk food when you’re operating with little sleep. When you don't sleep well, you tend to consume more carbohydrates and fewer fats and proteins, which can affect your nutrition goals. Sleep deprivation can also increase your risk of diabetes and unwanted weight gain, which can cause sleep apnea and other issues that can further hurt your sleep.

Many people in the Warfighter community (and even within society as a whole), are conditioned to believe sleep is a luxury. In fact, it’s a basic building block of health and well-being.

How to improve your sleep readiness

Sleep readiness is vital for health, performance, and well-being. And the better the sleep, the greater its benefits. That’s why proper “sleep hygiene”—practices that promote optimal sleep length and quality—is so important. Here is a 3-step guide to help you boost your sleep readiness!

Step 1: Make sleep readiness a priority!

Many people in the military culture see sleep as a luxury and not as mission critical. This belief might lead you to make excuses to put other activities before sleep. Sometimes, circumstances do exist—such as a newborn child or a mission-essential task—that you might need to prioritize over sleep, but the science is clear: You are a better Service Member, parent, spouse, worker, athlete, and overall person when you get good-quality sleep. This is why the first step to improving your sleep readiness is to make sleep a priority and choose it over work, social events, video games, or “just one more” TV show.

Many people in the military culture see sleep as a luxury and not as mission critical. This belief might lead you to make excuses to put other activities before sleep. Sometimes, circumstances do exist—such as a newborn child or a mission-essential task—that you might need to prioritize over sleep, but the science is clear: You are a better Service Member, parent, spouse, worker, athlete, and overall person when you get good-quality sleep. This is why the first step to improving your sleep readiness is to make sleep a priority and choose it over work, social events, video games, or “just one more” TV show.

Step 2: Study your sleep readiness patterns.

Do you know how much sleep you need to optimize your health and performance? One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to sleep. Each person has a different ideal sleep environment, time, and amount that helps them feel well-rested and energized. So, how do you know how much sleep is right for you? Most people don’t know or just go by the standard of 8 hours. What if that isn’t enough for you? Or what if it’s too much, but you’re up at night stressing about not getting enough sleep—when really you only need 7 hours?

The good news is: HPRC has 2 sleep-readiness tools to help you learn how long you naturally sleep when not interrupted and how different lengths of sleep impact your energy and focus. The first, HPRC’s sleep self-study, requires you to find a week when you can sleep as long as you need each night, without using an alarm to wake up. You try to eliminate things that might impact your natural sleep pattern, and you track when your body is ready to sleep naturally. By the end of the week, you should start to discover your “sleep sweet spot”: how long your body needs to sleep to feel rested, and what time your body is naturally ready to go to sleep. For specific instructions, go to HPRC’s Sleep Self-Study Guide.

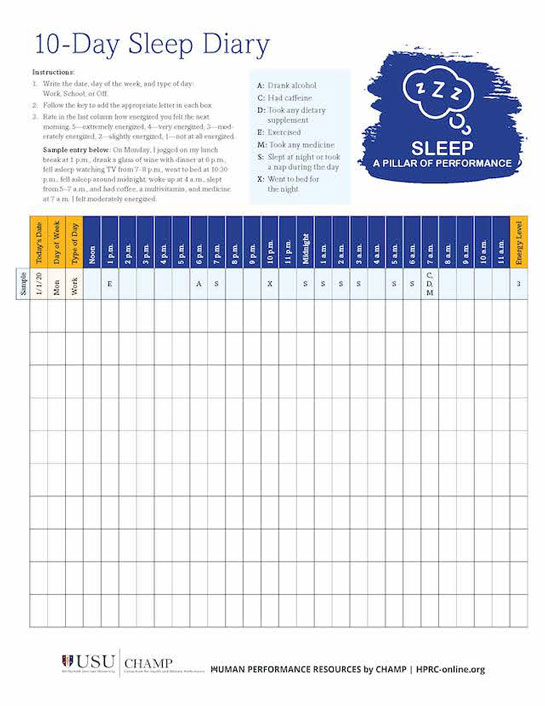

If you can’t find a week to do the self-study, you can begin to discover your sleep sweet spot by using HPRC’s sleep diary. Use it to track how long you sleep, things that impact your sleep (such as caffeine, medicines, and exercise), and your energy levels. What keeps you up at night? What helps you feel rested in the morning? When’s the best time for you to go to bed and wake up? Do naps help? The exact sleep recipe to get the best results is likely different for each person. Download the sleep diary below to study your sleep-readiness patterns.

Step 3: Practice good sleep hygiene

Unfortunately, you can’t make yourself fall asleep. Sometimes, the harder you try, the more you stay awake. Luckily, your body is designed to get the rest it needs, but it’s crucial to take the time to really understand how to set yourself up for success to get your optimal amount of sleep. The science-based sleep-hygiene tips below can help you make simple changes that will provide the optimal conditions for you to sleep. While science shows these tips work for most people, reflect on each tip to determine if it’s one you want to try, and then track its impact using your sleep diary.

Set yourself up for sleep throughout the day

- Maintain a consistent, regular routine that starts with a fixed wake-up time. Pick a time you can maintain during the week and on weekends. Then adjust your bedtime so you shoot for how much sleep you need (for most, 7 to 8 hours).

- Get early morning and regular exposure to sunlight. Increased exposure to natural light will help regulate your internal clock with nature’s light-dark cycle and help you be ready for sleep at night.

- Nap wisely but sparingly. Napping can be a good way to make up for poor or reduced nighttime sleep, but naps can cause problems falling asleep or staying asleep at night, especially if they’re longer than one hour or taken late in the day (after 1500 hours). If you need to nap for safety reasons (for example, driving), try to take a 30–60 minute nap in the late morning or early afternoon (for example, right after lunch)—just enough to take the edge off your sleepiness.

- Get your exercise. Exercise is essential, but it can make it hard to sleep if done too close to bedtime. Try to finish your exercise at least 3 hours before bedtime so you have plenty of time to wind down.

Practice smart sleep nutrition

- Caffeine in the morning and early afternoon can boost your mental and physical performance, but too much can degrade your performance. Up to 400 mg of caffeine (approximately 2 cups of coffee) is safe for everyday use, but more than that can cause insomnia, shakiness, restlessness, anxiety, or an upset stomach.

- Stop caffeine at least 4 to 6 hours before bedtime. Caffeine promotes wakefulness and disrupts sleep.

- Don’t go to bed hungry. A light bedtime snack (for example, milk and crackers) can be helpful, but don’t eat a large meal close to bedtime. Also, avoid spicy or fried foods at least 3 hours before bed.

- Don’t drink alcohol before bed. Alcohol makes you feel sleepy initially, but it disrupts and lightens your sleep several hours later. In short, alcohol reduces the recuperative value of sleep.

- Nicotine—and withdrawal from nicotine in the middle of the night—also disrupt sleep. If you need help to quit drinking or using nicotine products, see your healthcare provider for options.

- Avoid drinking lots of liquids or heavy foods right before bed that might disrupt your sleep by waking you to use the bathroom. Also, remember to empty your bladder before you go to bed.

Create your ideal sleep environment

Create a quiet, dark, comfortable sleep environment. Cover windows with darkening drapes or shades (dark trash bags work too), or wear a sleep mask to block light. Minimize disturbance from environmental noises by using foam earplugs, or use a room fan to muffle noise. If you can, adjust the room temperature to suit you. If you can’t, add or remove extra layers of blankets until you feel comfortable.

Create a quiet, dark, comfortable sleep environment. Cover windows with darkening drapes or shades (dark trash bags work too), or wear a sleep mask to block light. Minimize disturbance from environmental noises by using foam earplugs, or use a room fan to muffle noise. If you can, adjust the room temperature to suit you. If you can’t, add or remove extra layers of blankets until you feel comfortable.- Remove the smartphone, computer, laptop, etc., from your bedroom. Don’t eat or drink in bed. Keep discussions, especially arguments, out of the bedroom. Use your bedroom only for sleep and sex.

- Move the bedroom clock so you can’t see it. If you tend to check the clock 2 or more times during the night, or if you worry that you aren’t getting enough sleep, cover or turn the clock face around so you can’t see it (or remove the clock from your bedroom entirely).

Build good sleep habits

- Create a consistent bedtime routine that cues your body it’s time to sleep. This can include strategies to calm your mind such as prayer, paced breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, or mindfulness meditation.

- Start a regular gratitude practice using HPRC’s gratitude calendar. Some research has shown that those who regularly practice gratitude sleep longer by almost an hour and feel significantly more refreshed the next day, compared to those who don’t practice gratitude.

- Get out of bed if you can’t sleep. Keep your bedroom a calm environment for rest. Don’t try to force yourself to fall asleep—it will tend to make you more awake, making the problem worse, and it could make your bedroom a stressful environment. If you wake up in the middle of the night, give yourself about 20 minutes to return to sleep. If you don’t return to sleep within 20 minutes, get out of bed and do something relaxing. Don’t return to bed until you feel sleepy.

Seek professional help.

- Each of these tips is a best practice based on research, but they aren’t hard rules that will work for everyone in the same way. Consult with your doctor or a sleep specialist to help determine what will work best for you.

- If struggling with insomnia, ask your doctor about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for insomnia (CBTi), which has been shown to be an effective intervention.

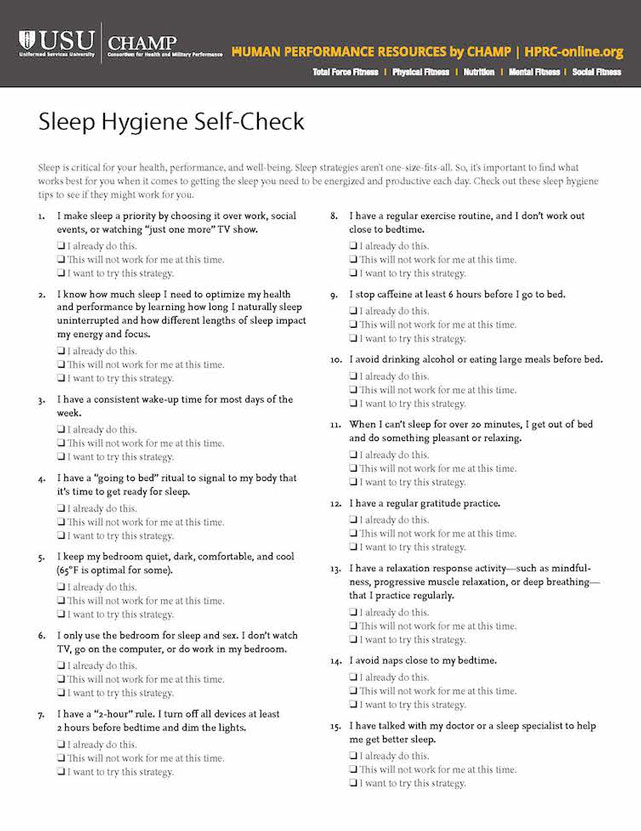

To help you or those you lead to reflect on the use of good sleep hygiene tips, download HPRC’s Sleep Hygiene Self-Check worksheet below.

Bottom line

Sleep loss causes your performance to suffer, whether you’re at a desk job, on a combat operation, or at home. Getting plenty of sleep helps you perform your best. Visit HPRC’s infographic on sleep and performance to keep these tips on top of your mind. If you can’t get a good night’s rest, read HPRC’s article about strategic napping to learn ways to manage your sleep debt.