- Headquarters, Departments of the Army, the Navy, & Air Force. (2017). Nutrition and menu standards for human performance optimization (AR 40–25/OPNAVINST 10110.1/MCO 10110.49/AFI 44–141). Departments of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force, Washington, DC. Retrieved 10 January 2020 from https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/AR40-25_WEB_Final.pdf

- Produce for Better Health Foundation. Insider’s viewpoint: Stay hydrated with fruits & veggies. Insider’s Viewpoint. Retrieved 24 October 2019 from https://fruitsandveggies.org/stories/insiders-viewpoint-stay-hydrated-fruits-veggies/

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, & American College of Sports Medicine. (2016). Nutrition and athletic performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 48(3), 543–568. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000852

- Karpinski, C., & Rosenbloom, C. A. (2017). Sports Nutrition: A Handbook for Professionals (6th ed.). Chicago: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

- Sawka, M. N., Burke, L. M., Eichner, E. R., Maughan, R. J., Montain, S. J., & Stachenfeld, N. S. (2007). Exercise and fluid replacement (American College of Sports Medicine position stand). Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(2), 377–390. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597

- United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. (2016). USDA Food Composition Databases. Retrieved 26 April 2017 from National Agricultural Library

- U.S. Army Public Health Command. (2011) Work/Rest and Water Consumption Table. U.S. Army Medical Department. Retrieved 10 January 2020 from https://home.army.mil/bavaria/application/files/4215/3926/1059/Safety_Water_Consumption.pdf

Key Points

- Don’t rely on thirst as a good indicator of your fluid needs; consume fluids throughout the day with meals and snacks to ensure adequate hydration.

- Drink 14–22 ounces of water at least 2–4 hours before and up to exercise or training sessions; urine should be pale yellow in color.

- Drink regularly or whenever possible during exercise, training, and operations. Drink 16–32 fl oz of fluid every 60 minutes during activity to stay hydrated.

- Performance will start to decline once you’ve lost as little as 2% of your body weight.

- To rehydrate (replace fluids) after exercise, drink liquids and eat foods that contain fluids. Consume about 20–24 fl oz of fluid for every pound of weight you lost.

- Drinking too much plain water or not consuming enough sodium can lead to hyponatremia (low sodium levels in your blood), a potentially serious condition.

Water is the most abundant component of the human body—around 50–70% of its weight—so your body requires fluids regularly to ensure its normal function. This chapter covers how to maintain your body’s optimal amounts of water and electrolytes at all times.

Fluid balance

Fluid balance is the amount of fluids you take in versus the fluids you lose, mostly through sweating, urinating, and breathing. It’s important to consume fluids regularly throughout the day to maintain your fluid balance and ensure your body functions normally. When you don’t drink enough water, your fluid output will exceed your fluid input. This can cause dehydration, impairing both mental and physical performance. Men and women have different hydration needs. However, fluid requirements also can vary depending on your workload, level of heat stress, and sweat rate. What and how much you drink before, during, and after exercise can greatly affect your performance.

When and how much to drink?

Military guidelines recommend 3–4.5 quarts (96–144 fl oz) of fluid per day for men and 2–3 quarts (64–96 fl oz) of fluid per day for women. Note: 1 quart is equal to 32 fl oz.1 As a general rule of thumb, try to consume half your body weight (in pounds) in fluid oz daily. Remember that all fluids from food and beverages count towards this goal. Fresh foods that contain high amounts of water include2:

- Broccoli

- Berries

- Cauliflower

- Celery

- Citrus fruits

- Cucumbers

- Lettuce

- Peaches

- Peppers

- Spinach

- Tomatoes

- Watermelon

You can maintain hydration by drinking beverages and eating foods high in water content throughout the day. However, each Warfighter’s fluid needs are different, so it’s important to learn to look for signs that indicate your own fluid needs. Be sure to adjust your intake when you’re working or exercising outdoors, especially when it’s hot and humid. If it’s very hot, drink fluids with sodium and potassium to replace electrolytes lost from sweating. The more physically active you are, the more fluid you need!

Dehydration

It’s essential to stay well hydrated during operations. Dehydration can negatively affect your physical performance, decision-making abilities, concentration, and mood. In addition, it can put you at risk of heat illness, including heat exhaustion, heat injury, and heat stroke, and even can be life-threatening.3,5 Fluid losses are greater during exercise with a long duration and when it’s hot or humid. However, it’s important to remember that you still lose fluids even when you don’t seem to be sweating much, such as at higher altitudes, when it’s cold, and during low-intensity physical activity.

Symptoms of mild-to-moderate dehydration include:

- Thirst

- Headache, dizziness, or light-headedness

- Dark yellow urine

- Dry or sticky mouth

- Decreased urine output

- Sleepiness or fatigue

- Constipation

- Dry skin

Symptoms of severe dehydration include:

- Extreme thirst

- Irritability or confusion

- Unconsciousness or delirium

- Very dark yellow or amber-colored urine

- Rapid breathing

- Rapid heartbeat

- Lethargy

Monitoring fluid losses

You can monitor your hydration status by noting changes in your body weight. To determine a body weight that reflects a well-hydrated state, weigh yourself (nude for accuracy) first thing in the morning—over several days—and calculate your average weight. To estimate fluid balance, weigh yourself (nude for accuracy) before and after exercise and calculate the difference, as shown in the following equation:

Total body weight (before) – total body weight (after) = fluid lost during exercise

Losing more than 2% of your body’s weight in water (Table 5–1) can result in poor performance, especially in hot weather.3,4

Table 5–1. Bodyweight Losses and Dehydration

| Starting Weight (lb) | Weight After 2% Fluid Loss (rounded to nearest lb) |

|---|---|

| 150 | 147 |

| 170 | 167 |

| 190 | 186 |

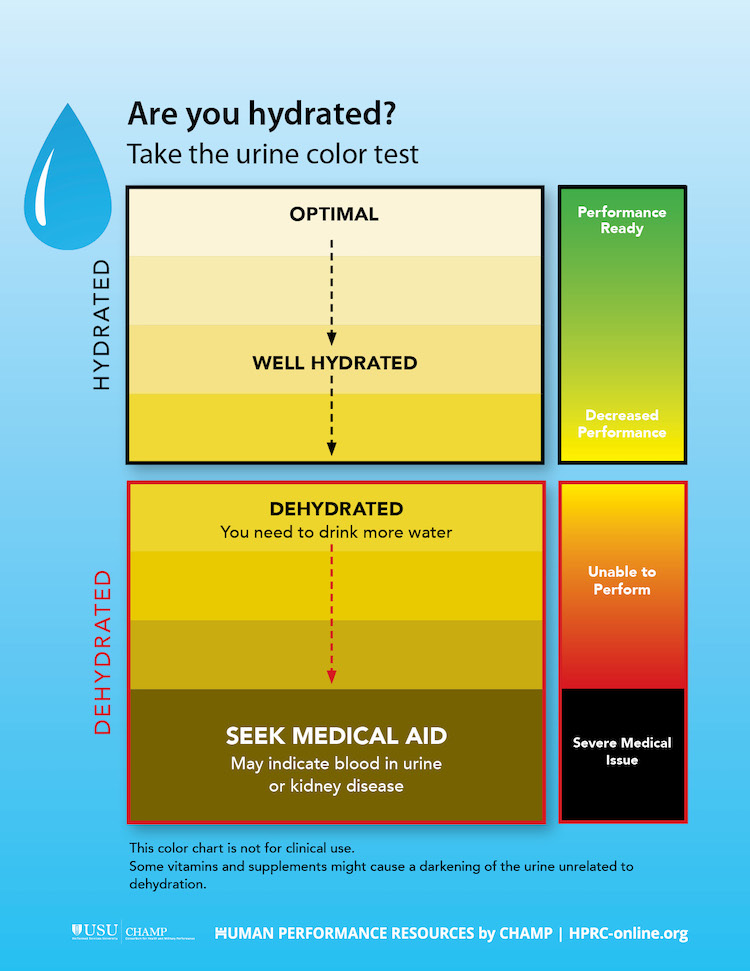

You can assess your hydration status by the color of your urine too. Pale yellow, almost-clear urine indicates adequate hydration. In general, the darker your urine, the more dehydrated you are. (Keep in mind that urine color can change for reasons other than your hydration status. For example, your urine can turn bright yellow if you’re taking B-vitamin supplements, especially ones high in riboflavin.)

Electrolytes

During activity, you mainly lose fluid through sweat. Sweat loss varies depending on age, type of training, physical fitness, clothing, and environmental conditions, as well as how you adapt to those conditions. Individual sweat rates for men and women can vary between 0.3 and 2.5 liters (about 0.3–2.6 quarts) per hour.3,5 In addition to fluids, you lose electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, and magnesium) and other minerals through sweat. Amounts vary, but they can be significant depending on your training status, dietary intake, genetics, sweat rate, and prior heat exposure. Electrolytes are important for muscle function, and loss of electrolytes can make dehydration worse than just fluid loss alone.

It’s important to consume foods and fluid-replacement beverages that contain electrolytes before, during, and after intense exercise or exercise of long duration to help maintain hydration. In particular, sodium can help your body retain fluids. Table 5–2 includes examples of foods that contain sodium. If you’re eating at a dining facility that has the Go for Green® initiative, choose foods labeled “High Sodium.” (Refer to Chapter 6 for more on Go for Green®.)

Table 5–2. Approximate Sodium Content of Foods6

| Food | Serving Size | Sodium (mg)* |

|---|---|---|

| Beef jerky | 1 oz | 590 |

| Canned chicken noodle soup | 1 cup | 700 |

| Cheese, cheddar | 1 oz | 180 |

| Cottage cheese | ½ cup | 400 |

| Ham, honey-smoked | 1 oz | 250 |

| Olives, black, canned | 5 large | 160 |

| Peanut butter | 2 Tbsp | 150 |

| Peanuts, dry-roasted, salted | 1 oz | 115 |

| Pickle, dill | 1 large (4” long) | 1,090 |

| Pretzels, hard | 1 oz | 350 |

| Soy sauce | 1 tsp | 300 |

| Table salt | 1 tsp | 2,325 |

* Actual sodium content can vary by brand.

You can eat dried fruit and other foods to replace potassium (Table 5–3).

Table 5–3. Approximate Potassium Content of Foods6

| Food | Serving Size | Potassium (mg)* |

|---|---|---|

| Apricots, Mediterranean, dried | ¼ cup | 430 |

| Avocado | ¼ of an avocado | 250 |

| Banana | 1 medium (7–8” long) | 420 |

| Cantaloupe | 1 cup | 430 |

| Figs, dried | 2 | 115 |

| Kiwi | 1 kiwi (2” diameter) | 215 |

| Lima beans, cooked | ½ cup | 480 |

| Milk, reduced fat | 1 cup | 350 |

| Orange juice | 1 cup | 500 |

| Orange | 1 small (2½” diameter) | 180 |

| Peanuts, dry-roasted, salted | 1 oz | 180 |

| Potato, baked, with skin | 1 small (1¾”–2½” in diameter) | 750 |

| Raisins | 1 small box (1.5 oz) | 320 |

| Spinach, cooked | ½ cup | 420 |

| Tomatoes, cherry | ½ cup | 180 |

| Yogurt, plain, nonfat | 1 single-serve container (5–6 oz) | 400 |

* Actual potassium content can vary by brand.

Hydration and rehydration: Fluid ingestion and timing

Before exercise

It’s important to be well-hydrated before exercise to reduce your risk of dehydration during or after exercise. In general, consume approximately 14–22 fl oz (about 414–650 ml) of fluid about 2–4 hours before and up to when you begin exercise. You also can use your body weight to estimate your fluid needs.3

During exercise

Drink 16–32 fl oz of fluid every 60 minutes during exercise for good hydration.7 Adjust your fluid intake based on your environment and how much you sweat because your fluid needs might be much higher in extreme environments such as heat and humidity, when it’s cold, or at altitude (as discussed in Chapter 11). During exercise, limit fluid intake to 1.5 quarts (48 fl oz) per hour.7 A “gulp” of fluid is about 1–2 oz.

When exercising less than 60 minutes, focus on drinking water. If it’s hot or humid, a sports drink might be better for hydration. For activity longer than 60 minutes, you can drink water, sports drinks, or a mixture of both. Sports drinks help maintain hydration, replace electrolytes lost in sweat, and provide fuel (in the form of carbohydrates) for your muscles during exercise. Look for a sports drink that contains 12–24 grams of carbohydrates, 82–163 mg of sodium, and 18–46 mg of potassium per 8 oz serving.1 You also can make your own sports drink with a few simple ingredients, as described in the article linked above.

While there are general recommendations, you still need to monitor your own fluid loss to ensure you replace the amount you lost.

After exercise

After exercise, consume foods and beverages to replace fluids and electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium) you lost. Over a period of several hours, you actually should ingest more water and sodium than you lost. If you know the change in your body weight after exercise, drink 20–24 oz of liquid per pound of weight lost to fully restore your fluid balance (Table 5–4).3

Table 5–4. Estimated Fluid Replacement Needs Based on Weight Loss3

| Weight Lost (lb) | Fluid to Replace Loss |

|---|---|

| 1 | 16–24 oz (2–3 cups) |

| 2 | 32–48 oz (4–6 cups) |

| 4 | 64–96 oz (8–12 cups) |

It’s important to choose foods and beverages that contain sodium to promote faster and more complete recovery. Drinking too much plain water or not consuming enough sodium can result in hyponatremia (low sodium levels in your blood), which requires immediate medical attention to reduce risk of serious illness or death. Hyponatremia typically occurs during physical activities of longer duration. Symptoms, which can be severe, include headache, vomiting, swollen hands and feet, fatigue, confusion, disorientation, and breathing problems. Keep in mind that some symptoms of hyponatremia are similar to the symptoms of dehydration, so be mindful of how much and how often you drink fluids.

On the flip side, if you consume too much sodium and not enough fluids, you’re at risk of hypernatremia (high sodium levels in your blood), but this is rare. Symptoms include thirst, headache, body cramps, and fatigue.

The guidelines discussed in this chapter will help ensure adequate fluid and electrolyte replacement and balance and reduce the risk of developing hypo- or hypernatremia.