The Total Force Fitness (TFF) framework is made up of 8 interconnected domains—social, physical, financial, spiritual, medical and dental, environmental, nutritional, and psychological—that support human performance optimization (HPO). As you get more fit in one domain, you reap benefits in the others. In this 2-part series, you will learn how the TFF domain of social fitness impacts your brain and overall health. And you’ll learn tools to build and strengthen your relationships..

The impact of social connections on health starts at birth. As a baby you depended on social interactions to develop your brain properly. Sensory stimulation—being held, seeing faces, hearing voices—at this early stage was key to your brain development and to building the skills essential to adult life. Without these experiences, you wouldn’t recognize faces, read emotions, or communicate using language.

Social fitness has many connections to a healthy brain. As an adult, you have a fully-developed social brain with regions dedicated to bonding, understanding other people, seeking relationships, and responding to social behavior. Service Members who enjoy strong connections with people perform better and live happier, healthier, longer lives.

Social interaction is naturally rewarding

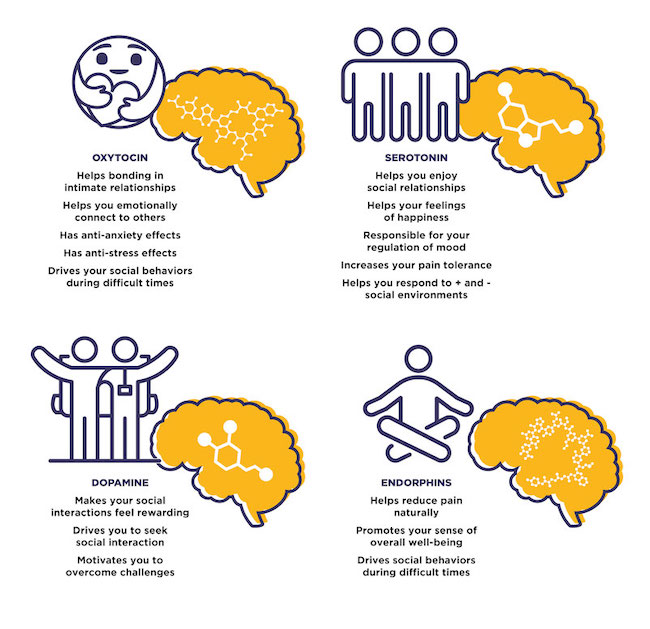

Biology ensures that you will have enough motivation to engage in behaviors essential to survival—eating, sleeping, overcoming challenges, sex—by making them pleasurable and desirable. It feels good to engage in these behaviors, which increases your desire to repeat them. Social interaction falls into this same category of behaviors that your brain finds pleasurable and desirable. Healthy interactions with other people promote your brain’s release of the chemicals oxytocin, dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins. These brain chemicals help control your social behavior and support your overall health and well-being, making social interaction naturally rewarding.

➤ Oxytocin is a brain chemical that increases in your brain in response to intimate relationships. It promotes bonding in close relationships, such as between a parent and infant or between romantic partners. Oxytocin is responsible for the calming effect on babies of cuddling and being held. As you grow older, oxytocin plays a similar role. Your brain releases oxytocin during periods of stress and pain to help you seek comfort and support. It makes it easier to endure and thrive during hardships. In short, oxytocin promotes bonding in your intimate relationships, protects your brain from stress, and drives social behavior during difficult times.

➤ Oxytocin is a brain chemical that increases in your brain in response to intimate relationships. It promotes bonding in close relationships, such as between a parent and infant or between romantic partners. Oxytocin is responsible for the calming effect on babies of cuddling and being held. As you grow older, oxytocin plays a similar role. Your brain releases oxytocin during periods of stress and pain to help you seek comfort and support. It makes it easier to endure and thrive during hardships. In short, oxytocin promotes bonding in your intimate relationships, protects your brain from stress, and drives social behavior during difficult times.

➤ Dopamine is the brain chemical responsible for making all the behaviors essential to survival rewarding and desirable. This includes social behaviors. Once your brain has learned to associate a particular behavior with pleasure, just anticipation of that behavior causes your brain to release dopamine. This increases your drive for action. When you are (or just feel) isolated, your brain starts to miss the reward that comes from social interaction and then releases dopamine to make you crave social behavior, creating a positive reinforcement cycle.

➤ Serotonin is another brain chemical responsible for the feel-good feeling that comes from hanging out with your friends or enjoying other healthy relationships. It stabilizes your mood, regulates your sleep-wake cycle, increases your tolerance to pain, and supports overall well-being. Differences in the brain’s serotonin system help explain why some people struggle in hostile work environments while others don’t experience the same problems. A hostile social environment can have disastrous effect on some people and little effect on others. But building supportive, nurturing, and healthy social networks typically benefits everyone.

➤ Social interactions promote the release of endorphins. These brain chemicals are your body's natural painkillers, but they also contribute to feelings of pleasure. Endorphins switch off the pain center in the brain, increasing your tolerance to physical and emotional discomfort. In other words, the painful experience is still there, but you don't feel it as strongly. So, the better the quality of your relationships, the better you tolerate pain. Stressful experiences also cause the release of endorphins, nudging you to seek social support during difficult times.

Social fitness boosts your mental fitness

When these 4 brain chemicals are in balance in your brain, you are likely to experience a direct, positive impact on your mental health. Well-connected people are more mentally fit. On the other hand, social isolation is a source of stress that leaves your brain more likely to develop mental-health disorders. Loneliness increases the risk of depression, anxiety, cognitive decline, and dementia. In addition, if you don’t have healthy relationships that satisfy your fundamental human needs, you miss the boost of mood and well-being that comes with all the positive chemical changes in your brain.

Social fitness promotes physical health and wellness

It isn’t only your brain that needs social interaction to thrive. Healthy relationships are essential for overall physical health. Well-connected people have stronger immune systems, less inflammation, and lower risk of heart disease. To compare the impact of loneliness with other health-risk behaviors, low social support throughout life increases risk of death to the same extent as smoking 15 cigarettes a day or being an alcoholic. And loneliness results in twice the risk of living a sedentary and obese life. In contrast, connectedness can help you improve your health and performance and live a happier, longer life. People around the world who live much longer than the world average share some common social factors: Belonging to the right tribe, putting loved ones first, and investing a lot of time in their children.

Seek connectedness

Connectedness can directly improve your performance as a Service Member. Reflect on the benefits of connectedness and identify those examples that increase your motivation to build and strengthen your relationships. Focus on your benefits and be as intentional about connecting with others as though your life depends on it, because it does. Part 2 of this series will offer some practical tools you can learn and use to enhance your social fitness.